“How do you know when a politician is lying? When his lips are moving.” Whether it’s through lies or obfuscation, diplomatic double-speak or straight up cover-up, governments the world over enjoy a complex relationship with truth. Yet there is something particularly dazzling about how the way the Russian government chooses to lie – whether to its own people, or to those abroad.

What’s truly special about the lies of Russian officials, what sets them apart from the rest, is both their audacity and the lack of criticism they inspire at home.

There have been some outrageous examples in recent years, but my two favourites are officials’ denials about Russia’s involvement in an armed conflict in east Ukraine and the way in which Russia is dealing with a current sports doping scandal.

Who can forget Russian President Vladimir Putin’s “I believe they got lost” when referring to active Russian servicemen detained on Ukrainian territory in the summer of 2014? It was hard to see the point when what is coming out of one’s mouth is so unbelievable as to be actually comic.

And that was just the tip of the iceberg as far as obfuscation on the Ukraine crisis goes. From hysterical news media reports about Ukrainian troops “crucifying children” to an entire network of fake sites used by state media outlets to claim, for example, that Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko got drunk and tried to fly to see Putin, lying about Ukraine, or any issue pertaining to Ukraine, is practically a sport.

Speaking of sport – Russia is currently in the middle of the largest doping scandal in its history. Officials started off by calling the doping allegations a “political hit-job,” before realizing the full scope of the World Anti-Doping Agency’s report, which includes such gems as direct allegations of security service officials personally compromising anti-doping efforts in the country.

When it became clear that denials would not work, Russian sports minister Vitaly Mutko relied on whataboutery, pointing out that doping is a global problem, not just Russia’s problem.

Whataboutery, of course, is the resort of an official who sees that at outright lie simply won’t work.

Russia’s troubled history is one of the greatest weapons in the whataboutist’s arsenal. By pointing out wars and famines, the Mongol Invasion, the bloody history of the monarchy and its equally bloody end, not to mention the horrorshow that was the first half of the 20th century, whataboutists can excuse all manner of problems, be they Russia’s rigid political system or underdeveloped civil society.

Yet just because Russia’s history is often used in this manner, doesn’t mean it doesn’t deserve a closer look.

Throughout the centuries, the Russian government in all of its incarnations – be it Imperial, or Soviet, or the modern government of the Russian Federation – has lacked any oversight or genuine counterweight.

Oversight implies accountability. Accountability, in turn, is a sign of “weakness.” And no Russian leader can afford to look even slightly weak.

A leader perceived as weak, be it the doomed Nicholas II, or someone like Mikhail Gorbachev, derided for his reforms, i.e. for being soft and refusing to hold the Soviet Union together by force, or else Boris Yeltsin, seen by the majority of Russians as a buffoon who kowtowed to foreign interests, is going to end up as wildly unpopular.

Both foreign observers and local ideologues frequently cast the Russian people as wild and unruly, desperately in need of a “strong hand.” This view of Russians as savages has served as a self-fulfilling prophecy – people who must be so firmly are denied any genuine responsibilities, and lack of responsibility in turn ensures chaos.

Meanwhile, Russia’s enormous size makes it especially hard to establish an effective system of governance. Moscow is the seat of the Russian government, but in places like Siberia or the Far East, it may as well be on the moon.

Russia’s population is diverse. What is perceived to work in Chechnya won’t fly in Tatarstan. Expectations for officials in Udmurtia are different for those in Krasnodar. Even Moscow and St. Petersburg, Russia’s two biggest cities, both situated in the European part of Russia, are ultimately different, even clashing worlds (and indeed Putin, a native of St. Petersburg, started his own Moscow career as a kind of Petersburgian “political outsider”)

The Russian saying “I’m the boss, you’re the idiot” is frequently used to criticise a top-down business culture, but the truth is, it is equally applicable to Russia’s political culture.

Today, the majority of Russians believe that systemic obfuscation goes all the way up to the office of the president. According to a poll from August 2015, as conducted by the respected Levada Center, 56 per cent of Russians believe that the people surrounding Putin are not truthful with him when it comes to what is happening in the country.

These numbers, in turn, make Putin’s astronomically high rating – in October 2015, it was nearly 90 per cent, and that’s amidst economic uncertainty and the devaluation of the ruble – appear to make a lot of sense. All of the problems in the country are laid at the feet of the people surrounding the president – not the president personally.

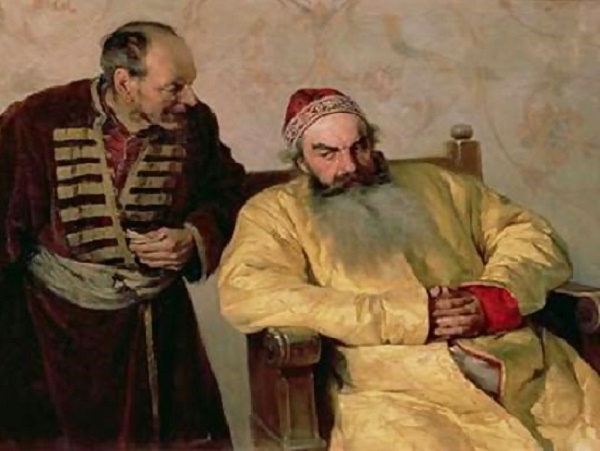

Eager-to-please Russian officials and the state-controlled media reinforce this narrative of the benevolent czar who must rule over a bunch of bad boyars.

Of course, polls are not necessarily 100 per cent effective in determining the mood in Russia. As Levada’s own researchers will frequently tell you, Russians are very good at saying what they think the government wants to hear.

This is the other crucial aspect of the culture of obfuscation in Russia – borne out of the aftermath of the 20th century’s repressions and Terror. Russia has sublimated its Stalinist past, when lies and denouncements were the norm, rather than dealt with it head on. Most visible Russian officials, including the Patriarch of the Russian Orthodox Church, are careful to not criticise Joseph Stalin too much, while a third of the regular people have a positive view of the man, according to this year’s polls.

And it is the legacy of Stalin, combined with so-called Gulag culture, when, as another popular Russian saying goes, “Half the country was imprisoned, the other half was guarding the prisoners,” that contribute to Russia’s current security syndrome, where information is dispensed strictly on a need-to-know basis, and lies are considered a perfectly legitimate means of attaining any number of political goals.

Besides Stalin, critics place a lot of the blame for Russia’s KGB-style treatment of information at the feet of Putin himself. Obviously, a former security official is going to hold true to the culture of obfuscation – and justify it.

That’s the reason why Putin can get away with first claiming that there were no Russian troops in Crimea when it was annexed, then going on to blithely stating that the troops were indeed present. For as long as the lying is accompanied by a geopolitical victory – or seeming victory – it is presented as perfectly normal.

State propaganda also plays a key part in legitimising dishonesty. In fact, it legitimises it so much that dishonesty becomes a kind of closed loop.

First the government sets out an agenda that deems that news should be “spun” a certain way, and that dissenting voices are unwelcome in mainstream media. Then the mainstream media becomes so uniform, so monolithic in both its style of reporting and the topics it choose to highlight (and omit), that disinformation rises through the highest echelons of government, turning the misinformers into the misinformed.

When Russia moved to annex Crimea in March of 2014, for example, German Chancellor Angela Merkel had a phone conversation with Putin after which she characterised the man as being “in another world”.

Putin was living in his own bubble. No counter-opinions were getting through. The system that Putin had presided over for over a decade at that point had evolved to filter out facts that were inconvenient.

This is why Russian officials are bewildered and even hurt when they face any kind of grilling abroad. The last decade in Russia has re-cast genuine dissent and debate as not just damaging, but distasteful and dishonest.

While most prominent western officials expect a fair degree of scrutiny and criticism – whether done in good faith or not – Russian officials of a similar rank are baffled and incensed by it. For them, being asked tough questions is a sign that there is a plot against them.

This is why the pro-Kremlin press gets away with casting every single vocal Kremlin critic as a turncoat and sell-out to Western officials – the thought of anyone having genuine grievances, let alone inconvenient truths, to share with the powers that be is seen as simply preposterous.

This trend began with the infamous “oligarch wars” of the 1990s, wherein news reporting became a handy tool for settling scores between powerful people, and grew to be a kind of unofficial policy as Putin consolidated power. At this point, it can well be said to be out of control, a genie that nobody in the Kremlin can stuff back into its bottle.

Of course, the truth can indeed make one vulnerable, especially if it’s an embarrassing one. But obfuscation only works as a short-term solution to various problems.

Not only does it ultimately disorient the very officials who are meant to control it, it also inevitably erodes the state’s moral authority.

In a multi-party system, where power is shared and politicians come and go, lies and accompanying scandals don’t cast nearly as much shadow on the government as a whole.

But in a system like Russia’s, lies can have a cumulative destabilising effect.

Putin has the trust of the majority of Russians. But the rest of the government simply does not enjoy such support. In fact, it could very well be argued that any potential mistrust of Putin is, at this point, being displaced onto everyone else in government.

An entire modern state riding on the moral authority of one man is ultimately vulnerable.