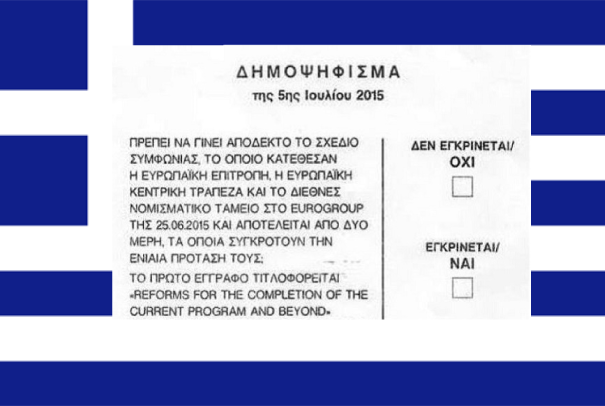

For many it appears confusing that there should be such popular support for continued membership of the Euro in Greece, given the brinkmanship of the current Greek government. But early indicators show a likely "yes" vote in Sunday’s referendum on whether to accept the plan put forward by the European Commission, the European Central Bank and the International Monetary Fund.

This in large part represents an understanding by most Greeks of the tough economic fall out that would follow “Grexit”. Here’s a rough run down of what would happen:

1. Greece would reintroduce the Drachma, which would immediately plunge in value against other currencies as foreign investors abandoned Greece en masse. For them the Euro exit would be a measure of Greece’s parlous economic prospects and they would fear what would follow – the Syriza government imposing a one-off tax on all foreign held assets, say, to get the economy back on it’s feet. The Greek government would make some effort to defend the currency using its €5.2bn of foreign exchange reserves. By buying Drachma with it’s reserve Euros it would try to offset all the selling by departing foreign investors retaining the balance between demand and supply for its home currency – but these would soon be exhausted.

2. In a 2012 paper the IMF estimated that the Drachma would be devalued by about 50 per cent against the Euro. Oxford Economics in February reckoned it would be 30 per cent.

This would devalue people’s savings, stopping consumer spending in its tracks. As consumers we tend to spend when we feel wealthy and save when we don’t. How much our savings are worth is a big part of this.

3. A devalued Drachma would also cause huge inflation. Companies importing sunglasses, say, would now have to pay their suppliers double; much of this would be passed onto the prices of the sunglasses. The IMF reckons inflation would boom by 35 per cent. Many essential items, of which Greece is a net importer - wheat, milk, meat – would balloon in price. (Exporters on the other hand, would do well out of this; those selling oranges to English supermarkets would have double the profits, when they converted them back to Drachma, which would help fuel Greece’s mid-term recovery).

4. Investor confidence would be shattered so neither the Greek government nor Greek companies would be able to borrow from abroad for several years. Debt is the cornerstone of the capitalist system (unfortunately), so this would be a problem. New roads to get people to work quicker (government borrowing)? New machines to harvest oranges quicker and more cheaply? Additional temporary staff to sell all those sunglasses ahead of the summer season (both private borrowing)? Forget about it.

5. With no additional bailouts the Greek government would have run out of money. With no money to pay pensions or government wages, whoever is in charge would have a hard time of governing.

6. The ultimate effect, reckons the IMF, would be a hit to GDP of 8 per cent. The Greek economy has already contracted by 25 per cent.

7. Creditors would likely agree to some sort of debt restructuring that would involve a “haircut”, corresponding to some level of debt forgiveness. The costs would fall mostly on official creditors including IMF, the ECB and the governments of other European economies, who are on the hook for most of of Greece’s external debt, currently about $500bn. Roughly $46bn is owned by foreign banks, but this is widely spread so should not cause too much disruption.

The alternative, a default on current loans while staying in the Euro, is pretty pointless. Because the loans were restructured in February 2012 to avert the Armageddon last time, the interest rates are relatively small (3 per cent of GDP). Greece need not start paying back the principal on most of eurozone loans until 2022. So it wouldn’t get Greece out of the hole, which is about how much they owe, not how much interest they must pay.

The problem is the conditions that are attached to the loans.

Each time a big loan is due for repayment, the "troika" of creditors – the IMF, the ECB and the European Commission (representing Europe’s various credit governments) attach conditions to the new loan. It’s like the bank manager saying, "I’ll renew your loan for another year, but on the condition you only spend £100 all year on clothes. Otherwise I won’t".

Why is the troika imposing these conditions? In part, because they want their money back. The Greek government won’t find the money for repayment until the economy recovers – as growth returns, tax receipts increase and the money collects in government coffers. But,they reason, if Greece doesn’t reform and continues to let people dodge taxes, take excessive pensions, retire too early and be payed a minimum wage that the state can’t afford the economy may never recover.

The Greek government has made a start. Forget about it’s debt interest payments and its primary budget is in surplus – it gets more in taxes that it pays out in public spending (pensions, teachers salaries, building hospitals etc). It is also running a current account surplus: it is exporting more than it is importing which, crudely, means money is pouring into the economy rather than pouring out.

But it needs to do much better if the troika is to get its money back. The current target is to increase today’s tiny surplus to 3.5 per cent of GDP by 2018 and onwards. The creditors – most notably the IMF – do not believe that the current reforms proposed by the government will achieve this.

Many economists believe that without this discipline from outside creditors, Greece, especially with the current government, would go back to its bad old ways of excessive spending.

The fracas that concluded on 30 June with Greece missing an IMF payment was a small skirmish in a much bigger fight. The argument was about whether Greece would adhere to creditor conditions in order to release the last tranche – €7.2bn – of bailout number two – total €130bn – that was extended in February 2012.

The real battle will be for the third bailout, required to keep Greece solvent as future payments come due – nearly €7bn to the ECB in July and August alone – which economists reckon will require between €30 billion and €50 billion.