Free speech debates don't usually feature that much disagreement. It's kind of an embarrassing family secret. You get a bunch of free speech campaigners together and they talk a lot about robust debate and adversarial politics and they mostly nod and agree with one another. Then everyone leaves feeling like maybe they let themselves down somehow.

The free speech panel at the recent Battle of Ideas was a case in point. Everyone on the panel was a good, robust, adversarial champion of free speech and we all firmly agreed about it. We warned that college campuses had become places where free speech was not allowed, where students were being wrapped in self-administered cotton wool and intellectual challenge was increasingly being compared to emotional trauma. We concluded that universities were creating a generation of timid, easily-offended censors, like the children in the flat next to Winston Smith, ready to report on their parents.

When questions went out to the audience, a man at the back stood up and asked if any of the people we'd been criticising had actually been invited to attend. "It feels a bit like we've got our own echo chamber here," he said. The panel – myself, Christina Hoff Sommers, Gia Milinovich and Tom Slater – blushed.

In our defence, it's actually very difficult to get the campus censors to talk. That's true almost by definition. Milinovich had tried to set up a debate for months with little success. The "safe spaces" lot rarely wish to defend their position. And those that will usually refuse to "share a panel" with anyone who holds certain views on sex work, transgender issues, political correctness, or something else. No-one is ever quite pure enough for them to be able to sit next to them.

When you do challenge them online it is almost impossible to have a meaningful discussion. You're told, as a white man, to shut up and listen to marginalised voices, but all they ever seem to say is "OMG I just can't even!" or variations on the theme. Their exchanges are dominated by a heightened sense of shock and snide bafflement without any content supporting it.

I found it nearly impossible to get anyone to talk to me about free speech when I wrote a piece for the Guardian on Goldsmith's Union's decision to block comedian Kate Smurthwaite on the basis of her views on sex work. No-one would talk to me; not the student union, not the feminist society, not the comedy society, no-one. The very request to speak was treated either as an act of harassment or a demand for special privileges. I asked people to speak more broadly about safe spaces – such as NUS president Toni Pearce – but none of them would get back to me. It is literally easier to speak to front bench politicians than student union officials.

That sense of victimhood is combined with a constant demand for political purity

Once you publish, it's different. They come at you hard. They call the paper demanding a retraction. They call you a liar on Twitter and try to get their followers to pile on you.

The censorship movement thrives off a sense of victimhood, he idea there are powerful forces denying them their room to speak. When journalists or debate organisers actively seek out their opinions, it is interpreted as aggression because it must be filtered through the required prism of conspiracy and suspicion.

That sense of victimhood is combined with a constant demand for political purity, whipped into a tribal frenzy by social media. Any deviation from the moral lines of the tribe is treated as harshly as possible, typically with Twitter users encouraging their followers to pile on the transgressor. The storms they create are man-made. They are not just the result of many individual decisions. Usually, they are whipped up and encouraged by a small number of prominent social media users.

But that comment from the man at the back still stung. Increasingly, you can see all these qualities – the clamour for victimhood, the sense of strictly-policed political purity, the encouragement of social media outrage – among free speech campaigners. We are starting to take on the characteristics of our opponents.

A few weeks ago, leading feminists Caroline Criado Perez and Julie Bindel dropped out the Feminism in London conference. A fellow speaker, Jane Fae, had been targeted by the usual censorship mob for views which, as is common with these things, had nothing to do with what she was debating at conference. Perez and Bindel's decision was crucial. Their decision to drop out raised equal pressure on the organisers from the free speech side as they had received from the censors. It showed there are as many consequences to dropping speakers as there are to keeping them in the face of protests.

And it was important that both speakers were from the radical feminist wing of the debate – the same wing as those demanding Fae's removal. It was a remarkable moment of solidarity and a telling one: what had previously been outrage at the censorship of one's allies was turning into a broader argument against no-platforming, regardless of which side the target was on.

In the same week, human rights campaigner Maryam Namazie was blocked from attending Warwick University. The outcry from high profile figures online was instant and overwhelming and the Student Union backed down. A couple of weeks later, the news emerged that Goldsmiths Student Union diversity officer Bahar Mustafa, who tried to ban white men from political meetings, was facing a summons to court on malicious communication charges – a reminder that the authorities can be just as foolish and thin-skinned as student activists.

You could hear the machine creaking. Student campaigners were beginning to see that free speech rules were not just privileged artefacts shoring up existing power structures, but a necessary precondition for political discussion of any sort. The liberal voices within feminism, anti-racism and trans-activism were starting to make their strength known. And the voices of censorship were seeing how effectively their own tactics could be used against them. It was a glimmer of hope, a moment in which bridges could be built and the seemingly unstoppable movement of the censorship lobby brought to a halt.

So what did Sp!ked, the self-positioned in-house magazine of free speech (and linked to the Institute of Ideas, the organisers of the Battle Of Ideas), do? It went on the attack. "Caroline Criado Perez is pro free speech?" it tweeted, before pushing out an article on how "she used the state to crush people for malicious messages". You may remember that Perez was the recipient of a barrage of rape and death threats on Twitter after she won her campaign to have women featured on bank notes. Sp!ked evidently thought her desire to fight back against those threatening to kill her was an attack on free speech, rather than an affirmation of her own right to it.

Far away from the front lines of the censorship debate, Sp!ked could not even see its contours

The website's editor, Brendan O'Neill, fired out a piece attacking the new figures standing up to the censors. "On one level, this feels good," he admitted. But these people were only "defending free speech for people they like... They aren't defending freedom of speech; they're defending friends' free speech."

It was a revealing comment. It showed, first of all, that Sp!ked was completely cut off from what was going on in the free speech debate. They had missed the fact that Perez and Bindel were not standing down in solidarity with their ideological friends, but their opponents.

Far away from the front lines of the censorship debate, Sp!ked could not even see its contours. It was lost in its own rhetoric, unaware and unable to see that identity politics advocates themselves were doing the majority of the fighting against the censors, while they fired off tweets questioning their commitment.

The Sp!ked response is its own form of purity, not so different to that exhibited by the censors. Some of Bindel's supporters backed No More Page 3, they said. Some of Namazie's supporters opposed Islamic preachers on campus. For any potential convert they could see only a potential traitor.

And perhaps there is another quality of the censors in there too – an underlying sense of victimhood. Free speech campaigners are now used to being on the back foot, fighting against powerful authoritarian trends which seem to better fit our times than the instinctive liberalism of the past. Perhaps free speech advocates have begun to emotionally cling to that oddly satisfying sense of identity one can find on being the underdog.

Or perhaps we're just better at fighting than working together. Maybe the type of person who praises adversarial politics is usually psychologically ill-equipped to cooperate with those whose views they find objectionable. Perhaps the notion of challenging ideas is more comforting to them than engaging with them.

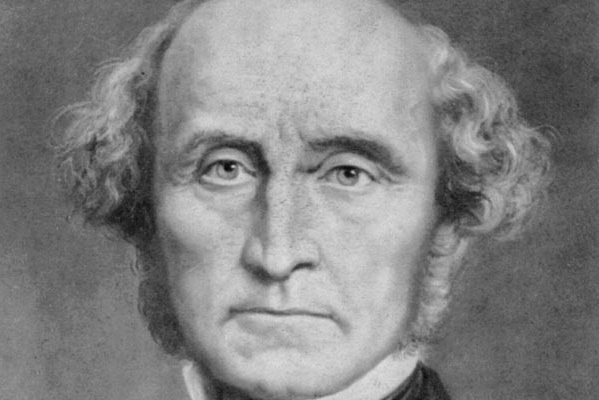

It's also possible that, just maybe, it was never about free speech for some of us. Occasionally you get the impression that free speech is just a bludgeon for liberals and libertarians to use against identity politics. That would be a disaster, because the front line in the free speech debate is not at the Battle of Ideas. It's in feminism, anti-racism and trans-activism. If free speech advocates look like anti-feminists daubed in John Stuart Mill battle paint we're not likely to be very effective.

The pull of political purity and victimhood is as strong in free speech advocates as it is everywhere else. If we don't start working with those we disagree with, we will remain on the back foot.