You can tell we are in the run up to what may be the most significant global climate change talks in almost two decades, beginning in Paris in November: think tanks, NGOs, the business community and media of all hues bombardus with reports and analysis that attempt to provide a fresh take on a subject that, while crucial to us all, is becoming somewhat well-worn.

Of all the recent studies, perhaps the most effective are those that have focused on the most immediate impacts of an issue that is usually discussed in terms of what will happen at the end of this century.

One problem with focusing on the long-term outlook, albeit one that may be very gloomy indeed and directly affected by what we do now, is of course, that most people alive now will no longer inhabit the planet in 2100. Even if no one likes to think of the children of the future facing the consequences of climate change, it’s still a hard thing to visualise. Another oft-cited problem is that 2100 is a full 17 five-year electoral cycles away, so what happens then is not necessarily regarded as a top priority for politicians in search of votes today.

In any case, the year 2100 is an arbitrary date in climate change terms, that risks distracting attention from the harsh reality that major effects won’t wait until the end of the century to materialise. And those effects will not be restricted to obvious impacts, such as heat stress, drought, storms and flooding.

Already today, we are seeing how extreme weather events affect a heavily interconnected world. For example, some studies have drawn a link between the Russian heatwave in 2010 and the Arab Spring uprisings that started shortly afterwards.

The heatwave led to a 30 per cent fall in the yield of Russia’s wheat harvest, triggering higher wheat prices across the globe. Those contributed to higher bread prices and food shortages in Egypt, triggering food riots and adding to wider public dissatisfaction with the Mubarak regime, which was toppled in the 2011 revolution, amidst a wider wave of upheaval sweeping across the Arab world.

It’s not too much of a stretch to seethe continuing chain reaction extending to the current instability in the Middle East and the wave of informal mass migration to Europe.

The Arab Spring uprisings helped trigger the civil war and power vacuum that now exists in Libya – and that in turn allowed Libya to become a conduit for migrants crossing the Mediterranean to enter the European Union. So, on that basis, a Russian heatwave in 2010 could be said to have played a role in shaping the nature of an immigration crisis in 2015.

You don’t have to believe the Russian heatwave was a direct result of global warming to accept the premise that an increase in weather extremes–which climate change scientists say will accompany global warming – could have profound effects on human populations, even in the relatively short term.

Providing a meaningful and easily understandable analysis of such complex and hard-to-predict linkages is a tough task.

But if anyone can, then insurers handling global risks probably stand as good a chance as anyone of doing it – after all assessing risks that are hard to quantify or predict is a large chunk of what they do for a living. And since global businesses are happy to rely on insurance companies to provide cover for their everyday risks, what insurers have to say about climate change should be deemed worthy of attention by the captains of industry – and the rest of us.

So research published recently by Lloyds of London, the insurance market, provides an eye-catching addition to the climate change debate. In a study called Food System Shock, published in June, a team from Lloyds, led by Trevor Maynard of the market’s exposure management division, looks at the potential consequences if a series of plausible climate change-related events – initiated by a shift in the El Niño ocean current – happened at the same time.

The result could well be economic and social crises across the world.

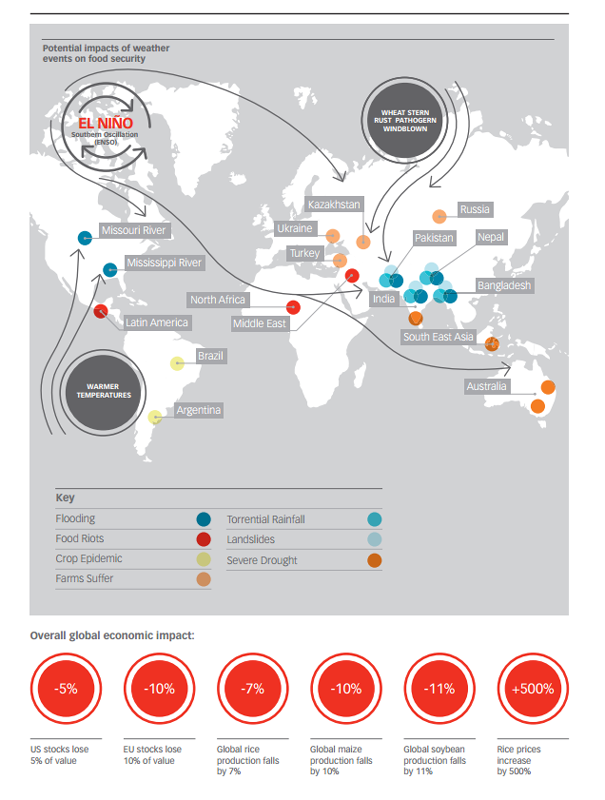

A strong warm-phase of the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) develops in the central equatorial Pacific Ocean. Flooding develops in the Mississippi and Missouri rivers, reducing production of maize in the US by 27 per cent, soybean by 19 per cent and wheat by 7 per cent.

Severe drought reminiscent of 2002 hits India, while parts of Nepal, Bangladesh, northeastern India and Pakistan are hit by torrential rainfall, flooding and landslides. Severe drought affects eastern and southeastern Australia and Southeast Asia. In India, wheat production is reduced by 11 per cent and rice by 18 per cent. In Bangladesh and Indonesia, rice is reduced by 6 per cent, and rice production falls in Vietnam by 20 per cent, and by 10 per cent in Thailand and the Philippines.

In Pakistan, wheat production is reduced by 10 per cent due to flooding. Australian wheat is reduced by 50 per cent by drought. Asian soybean rust expands throughout Argentina and Brazil, causing an epidemic. In Argentina, soybean production is reduced by 15 per cent, with a 5 per cent drop in Brazil. The Ug99 wheat stem rust pathogen is windblown throughout the Caucasus and further north; Turkey, Kazakhstan and Ukraine suffer 15 per cent production losses in wheat, while Pakistan and India lose an additional 5 per cent on top of existing flood and drought damage. Russian wheat production declines by 10 per cent.

Wheat, maize and soybean prices increase to quadruple the levels seen around 2000. Rice prices increase 500 per cent as India starts to try to buy from smaller exporters following restrictions imposed by Thailand. Public agricultural commodity stocks increase 100 per cent in share value, agricultural chemical stocks rise 500 per cent and agriculture engineering supply chain stocks rise 150 per cent.

Food riots break out in urban areas across the Middle East, North Africa and Latin America. The euro weakens and the main European stock markets lose 10 per cent of their value; US stock markets follow and lose 5 per cent of their value.

A bleak scenario then, but could it really happen?

Well, it’s based on a combination of just three catastrophic weather events happening simultaneously around the world – andthe Lloyds team says that’s not particularly far-fetched.

In fact, what really adds heft to the study is that, while the probability that the events outlined occur together may seem low, the authors say that this risk, right now, is still “significantly higher” than once in every 200 years.

That’s a significant figure. It is the benchmark risk level used within the insurance industrywhen assessing if insurers have enough money in their coffers to pay out against the most extreme events.

In other words, the insurance industry regards the risk of something happening more often than once every 200 years as significant enough to require action on its part. It probably won’t happen in the next couple of years, but it just might – and something more limited but still costly in human (and financial) terms is even more likely to happen.

The study’s authors accept that the difficulty of obtaining accurate data on some key components, such as global food stocks, introduces uncertainties into its scenario. And they are keen to stress their case study is no way intended as a prediction of future events. But they also point out that things are more likely to get worse than they are now, rather than better.

Risk probabilities are not static. If global warming continues, as most climate change scientists expect, then the probability of extreme weather events – and thus of extreme economic and social events as well – will increase.

At the same time, other factors such as growing global population and a switch to meat eating in developing countries such as China continue to reduce the amount of land available for crops, so increasing the likely effects of any climate-related disruptions on the food chain.

The idea of highlighting all this is not to scare the living daylights out of us. But the Lloyds team does believethe insurance industry, and society as a whole, need to be prepared for problems that may be waiting just around the corner.

Maynard says the next grand challenge for scientists is to bring together physical, economic and social modelling of the effects of global warming to help us better fight its worst impacts.

He also suggests that, in relation to climate change, the scientific community could benefit from adopting some insurance industry attitudes.

“It has always concerned me that our use of the word ‘conservative’ has the opposite meaning in insurance to its meaning in science. Scientists are ‘conservative’ if they constrain their worst fears, and wait for more evidence before communicating them; therefore, ‘conservative’ predictions tend to understate risk – they are less than best estimates. In insurance, ‘conservative’ reserves are higher than would be required by best estimates. In matters of risk assessment, I feel the insurance point of view is more appropriate,” says Maynard

Whether you believe global warming is man-made or not, preparing for the worst – as insurers do routinely – may not be such a bad idea.