The return of analogue - how vinyl went mainstream

In a cutting room near Mark Ronson’s studio in central London, Darrel Sheinman is explaining what a swarf fire is. His business, Gearbox records, specialises in all things vinyl. They record, make and produce music especially for vinyl, consulting for both major record labels and unsigned artists wanting to release their own LP. Gearbox is so dedicated to increasing the popularity of records they're even in the process of manufacturing their own player.

Their prize technique is direct to disc; the process of recording live music straight to vinyl, in real time. The music travels from the recording studio to a lathe, where the heated stylus carves out the groove in the record. As the roaring hot needle burns into the disc, the highly flammable nitrocellulose being dug out of the lacquered record can build up and ignite, setting alight to not only the record, but the entire cutting room if you’re not careful.

"When you’re listening to vinyl you’re surfing this analogue wave, this nice long smooth line that’s unbroken"

Mainly used for classical and jazz recording, direct to disc is a method where live music is directly recorded to vinyl, no editing, no compressions, no mastering.Herbie Hancock’s “Directstep” from 1978 is one of many legendary albums recorded using the direct to disc technique.

In an age when recording music couldn’t be easier, why would anyone want to invest in a format many think of as redolent of a bygone time and redundant in today’s industry?

“When you’re listening to something digital, you’re listening to all these little samples, these chopped up things.” Explains Adam Sieff, operations manager at Gearbox. “But when you’re listening to vinyl you’re surfing this analogue wave, this nice long smooth line that’s unbroken."

Adam has an extensive track record in the music industry. Formerly Director of Jazz UK & Europe at Sony Music, in 2011 he was awarded the Music Producers Guild Unsung Hero Award. Adam’s passion for vinyl is evident in the way he speaks about it, often picking up on technical points made by Darrel and fleshing them out with dreamy and enamoured language.

Brought together by a love of jazz, Gearbox now produces a variety of LPs. Everything from Nico’s 1971 BBC session to Kate Tempest’s Brand New Ancients; a classic story of two intertwined families told in beat verse, soundtracked with cello, violin and percussion. One of their most recent releases is by Applewood Road, a troupe of songwriters who first meet in Nashville, a city whose presence is at the core of their sound. The LP was recorded at Welcome to 1979, an analogue studio in Nashville, and perfect partner to Gearbox’s tape-to-turntable philosophy.

The Rise of Records

In 2015, the demand for vinyl reached a 21-year high as the industry sold over 2.1 million copies over the course of 12 months. Compare that to 2007, where only 205,000 records were bought, and you can see how the industry is going from strength to strength.

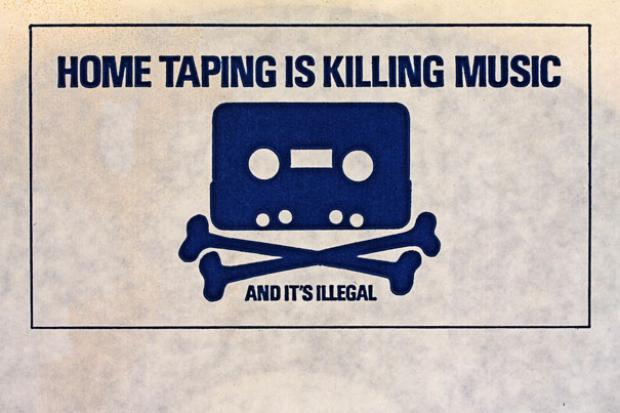

It’s the only format alongside streaming that’s managed the fair well in the post-Napster age. For years now CDs have been in decline, but recently even digital downloads have been dying alongside their compact cousins, with sales down 13.5 per cent last year.

It’s interesting that that only two formats still managing to turn a profit are at opposite ends of the spectrum. On the one hand, you have streaming; a subscription-based service where listeners never actually purchase anything, and on the other you have vinyl, a product that’s physically cumbersome and needs specialist equipment to listen to, but you can at least hold it in your hands.

The reason for the vinyl’s success might be it's ability to fill a gap in the market left wide open by the rise of streaming: investment. Subscription services are a great way of offering easy ways to access music. After all, the same music is still available for illegal download, but you have to find it and that can take some time. And why would you pay for a digital download, when you’re not even sure what you’re getting for your money? In practice, streaming is the same as buying a licence. You don’t actually own the download like you would a book or CD, and in the small print of your user agreement licence, you’ll find a whole host of terms and conditions restricting what you can and cannot do with your download.

That’s a lot of uncertainty for an industry we’re spending more and more of our money on. In 2014 British consumers came second for the amount spent on music per capita, beaten only by Norway. If we’re still willing to spend money on music, it better be something that’s going to keep its value. And with limited, gatefold, weighted and coloured editions, vinyl has found a way of creating a sought after product that isn’t likely to diminish in value over time.

It's not the only reason why vinyl has become popular again. For musical puritans, otherwise known as audiophiles, the reason why vinyl is considered better than other formats is the quality. Partly down to how basic the technology is, it's naturally devoid of the same compression, conversion or limitations subjected to digital recording. In essence, it’s the closest thing to an actual recording.

“Cutting a record is all about land management” Darrel says. “It’s fitting a certain fixed amount of music in a finite amount of space.

A lifelong jazz fan, Darrel’s collection of Blue Notes records now resides in the Gearbox studios. What began as a hobby, has now become a full-time business employing a team of experts. Before setting up Gearbox in 2009, Darrel was in maritime security. Drumming since the age of 12, he’s always had an affinity with jazz. Both technically complex and intricate, what attracted Darrel to jazz is the same as what attracted him to vinyl – how do you get the best sound?

But it was a hip-hop gig that inspired him to put the two together.

“I went to a N*E*R*D concert. It was a fantastic live performance that was really tight and I just got thinking that there’s so much good live music out there that hasn’t been put onto the best format possible."

He tried to approach the band’s management about securing the rights to the live performances but without the right contacts it proved too difficult. That’s when he decided to look at archive recordings and other ways of putting live performances onto records.

Another strand of the business is taking old live performances, usually hidden away in the archives of the BBC, and bringing them to life again. Technically new releases, as they've never been available to buy before, the recording are spruced up with some mastering and custom artwork, and sold to a new generation of fans.

“It’s actually quite difficult; a lot of people think producing a record is very much like producing a digital copy of something when it isn’t.” explains Darrel. “You can’t listen to ones and zero which is what happens with digital. It’s always converted to analogue. “

The technical competency it takes to produce vinyl of this quality requires everything to be impeccable. The Gearbox studio is packed with original, of the era, equipment. Each piece is either the last of its kind, with most machines cannibalised for parts nowadays, or significant enough for a museum and most are worth more than a basic annual salary.

“Vinyl cutting and mastering is the last part of the creative process not the first part of the manufacturing process”

A top of the range domestic HiFi (which tend to be more expensive and better quality than ones available in commercial studios, due to the budget limitations of record companies. according to Darrel plays back recordings through hemp cone speakers. Each record is blasted by an ultrasound record cleaner, which fires a light cleanser at the record to remove dirt and static. Darrel knows the whole process inside out, including what happens once the master leaves them for the record plant.

"After we do the master, the lacquer master is sent off to be galvanised and processed in an electrolyte bath. Then the plant silvers them with a nickel plate. That nickel plate becomes the negative which is used to make a positive from and that creates the stamper. A puck of vinyl material is then put on top of the positive, with the label on, and is fused by a high temperature, so the label isn't glued on like most people think. The stamper presses it down and creates the imprint. Then they trim the edge and you have a nice thing that goes off and gets cooled down. But before you even get to that point you have a test pressing which takes about four weeks and is used to check for any pops, blips and clicks. That’s the quality control stage. It's only after that you go into the final stamper stage "

Working with technology that is no longer manufactured and consists of moving parts makes it susceptible to mechanical faults that can be near enough impossible to remedy. These issues can have a knock-on effects that producers end up having to compensate for in other ways.

“Vinyl cutting and mastering is the last part of the creative process not the first part of the manufacturing process.”

It can be the least likely of things that end up having a knock-on effect. During one recording session, Darrel was having an issue and couldn’t figure out what was causing it. The needle kept jumping around and he was getting an unusual amount of phase. He was nearly at the stage of giving up when he got in contact with Sean Davies, a legendary lathe restorer. Sean is one of the last people who worked on vinyl the first time round. As he ran through a list of possible causes, Sean suggested that Darrel change the dampening; a little pot behind the stylus filled with oil.

It turned out the thickness of the oil was causing problems. When the lathe was restored, the oil was changed from the original grade one noble oil to a modern equivalent. But that wasn't good enough. After hunting around,Darrel managed to find the original oil that was used for tape machines and increased the viscosity, which solved the problem.

“It’s a real detective story.”

Gearbox’s method of precision and dedication makes for a great sound, but it doesn’t transfer well when it comes to mass manufacturing – where price is the only thing that drives output.

Vinyl is a booming market and record companies are only too keen to start turning a profit from it. But just because it comes on a disc doesn’t mean it’s going to sound good. The small market subset Gearbox have found themselves in, is due to an oversight by the major record companies. When most of them dropped vinyl from their catalogues opting for digital instead, they also lost the appropriate skillset and knowledge.

“There are some not very well made records released, often through third parties, often using poor quality MP3 files, which are being mastered using all sorts of terrible things. Sleeves that have literally been Xeroxed up.” Adam noted. “A lot of the major’s think, if it’s round and roughly flat and comes in a cardboard thing with nice colour people will buy it.“

Reissues are popular because they bridge the two types of record buyers; new releases and second-hand albums. They’ve also played a big part in the resurgence of the industry as a whole. After Urban Outfitters began kitting their stores out with a limited number of reissues, 12-inches became part of the cultural landscape once again. “It was those Stooges albums, that Velvet Underground album” commented Adam.

As the format really took off, Urban outfitter's chief administrative officer Calvin Hollinger told Wall Street analysts that his company was the biggest disturber of records. Several media outlets picked up on it and ran stories crediting the fashion chain for making vinyl cool again. But something didn’t feel quite right. While Urban Outfitters might have brought vinyl to a new generation it certainly wasn’t just on-trend millennials who were buying the majority of it. Billboard did some investigating and found Amazon were actually the biggest sellers.

That hasn't stopped other retails trying to get in on the action. Last year Tesco announced they were to start selling a selection of vinyl across 40 of their UK stores for the first time in the supermarket’s history. After trailing a range in the summer of 2015, the supermarket decided to sell a mix of new and releases, ranging from Prince’s Purple Rain, ELo’s Alone In The Universe and the Guardians Of The Galaxy Soundtrack, which gives you an insight into the type of people Tesco are trying to target.

If that wasn’t enough to convince you of vinyl’s longevity, last year the Official Charts Company announced the launch of a new vinyl chart. Again the results indicate two types of buyers, dads buying up the records they were forced to through out the first time and music fans who want a physical incarnation of their favourite albums. Last week’s top 40 consisted of a mixture of mainstream new releases Adele’s 25 and Kendrick Lamar’s To Pimp a Butterfly to dad classics like The Eagles' Hotel California and Rumours by Fleetwood Mac.

Using an old format doesn't mean being regulated to out of date technology. At the CES convention last year, both Panasonic and Sony unveiled new record players that married the best of high-quality audio associated with vinyl with the ease of digital. Bluetooth capabilities, the ability to rip albums into Hi-Res Audio files and smartphone plugins are the focus of this new generation of record players. It's a development welcomed by Darrel and his team.

"It feels they understand it’s still a niche interest and in order to make it bigger, everyone involved needs to give it a helping hand."

As customers shift towards a new way of listening, are records simply a trend? Slow listening, first coined by Michaelangelo Matos, an American journalist and author of The Underground Is Massive, is a movement aimed at restricting listening by focusing on just a few tracks or albums a day. In contrast to the constant grazing enabled by streaming and the internet as a whole, the sudden resurgence of records might play an important role in us listening to albums as a complete body of work again.

That's not to ignore what streaming has done for us in the age "post-internet" music; it's let us combine and create our own genres without being restricted by location, income or access.

Vinyl records have gone full circle. Turning from mainstream to indie and back again, it seems vinyl's latest incarnation might have more staying power than the last. This time, the recent revival isn't part of a wider game of technology trumps; where new formats are hailed as the next big thing only to be discarded in a heap of playbuttons, minidiscs and elcasets. >Vinyl will continue to play a role in how we listen to and collect music, on the condition that it sticks to what it knows best. When the format first disappeared into the mire during the 1980s, it was because it was the only format available. So when shiny compact discs came along, all slim and well, compact, vinyl didn't stand a chance. This time round, they're playing the outsider game. Records are big. They take up space. They're easily scratched or damaged, they even need specialist equipment to listen to them and that's exactly why we're buying them.

The returns on other formats are limited. Streaming is fleeting; it's all about what we're listening to right here, right now. We can add music to playlists and share it with friends but we can't really store it anywhere. We pay one amount for everything, regardless of whether we listen to one artist more than another. Like an all you can eat buffet, streaming enables us to constantly graze.

Vinyl allows us to invest in our favourites. Buying a record is the same as showing commitment. It's a way of saying 'I really like your stuff and think I'll continue to do so for a long time'.