Colombia’s president, Juan Manuel Santos, has signed a peace deal with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (or FARC), ending the longest war in the Americas. Signed using a pen made from a bullet in the Caribbean city of Cartagena, the agreement formally ends 52 years of bitter conflict which has left 260,000 dead and nearly 7 million displaced, with state aligned paramilitaries contributing to the violence.

The FARC, Latin America’s last insurgency with a nationwide reach, took up arms in 1964 in defence of the country’s vulnerable peasant population but later turned to the drug trade, kidnapping, and extortion to fund their political ambitions. Following a decade of sustained US-backed military offensives that left them weakened, the rebels were led from the jungle to the negotiating table in 2012.

After four years of tense negotiations, the peace deal includes accords on rural reform, combatting the drug trade, reparations for victims, transitional justice, and political participation for the 7,000 rebels.

Though the agreement still needs to be ratified by a national referendum, in Bogotá, Colombia’s capital, people took to the streets to celebrate a step towards lasting peace in a country that has only known war for generations. Little Atoms asked them about their hopes for peace.

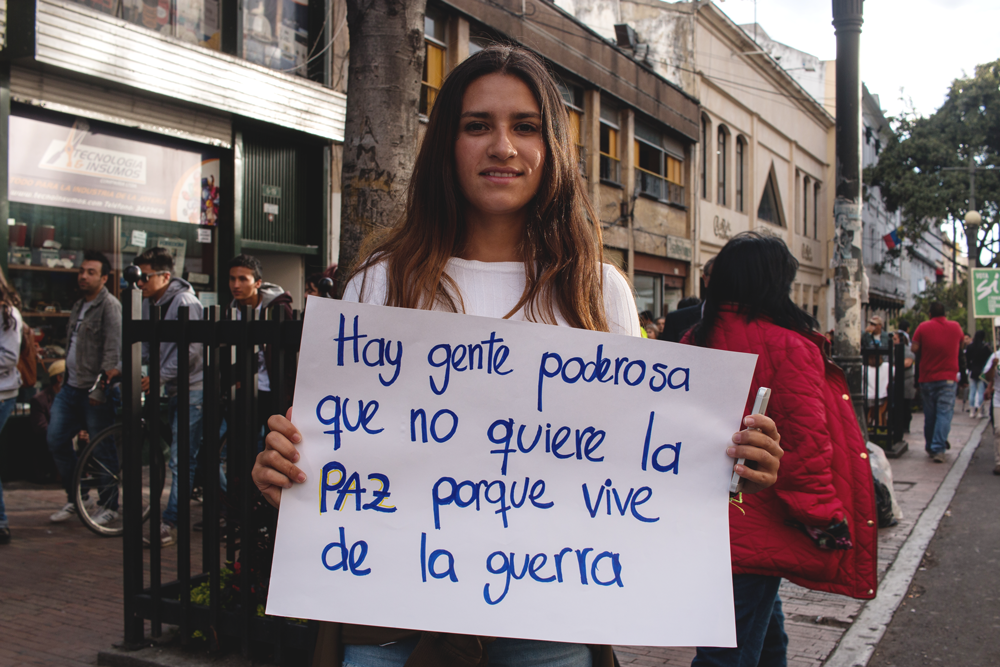

Natalia Calderon, 24, a publicist from Bogotá carries a placard reading “Some powerful people don't want peace because they make their living out of the war.” Natalia’s grandparents moved to Bogotá after being forced out of their rural homes by the FARC forty years ago. “Never in my life have I known my country not in war, without the military in the streets, without kidnapping, without extortion,” she said. “For me, this is the start of a new Colombia.”

A group of traditional Colombian carnaval dancers join the thousands of people celebrating the end of the longest war in the Americas.

Andrés Sánchez, 21, a law student from Bogotá, grew up with the conflict. “Today is the most important day in the history of Colombia, and I would ask No voters to think about the consequences of what they are asking for. Our country deserves the opportunity to start a new chapter.”

Carla, 51, who did not want her surname published, will be voting No in Sunday’s referendum. “Every human being wants peace, but not a false peace.” The No campaign is led by hardline former president Álvaro Uribe, who built his presidency on a brutal military campaign against the FARC. Uribe is currently under investigation for involvement in paramilitary massacres but remains a popular figure in Colombia’s divided political landscape. Many are opposed to the deal because they feel the FARC should answer for their crimes.

Supporters of the Yes campaign wave signs in front of Bogotá’s cathedral. Though demonstrations across the country reflected the support for both campaigns, in the capital the mood was celebratory, with many more Yes voters taking to the streets. No campaigners outside Bolívar square complained they were denied entry by police.

Carlos Ruiz, 63, poses with his bicycle modified with a model M16 assault rifle. “There are many uses for guns, but I think the best is a bike,” he told Little Atoms. Ruiz says he will vote Yes in Sunday’s referendum. Polls were close until a recent poll predicted a comfortable win for the Yes camp.

Crowds gather in Bogotá’s historic Bolívar Square, in front of the Palace of Justice. In 1985 the palace housed one of the darkest chapters in the history of the conflict when then the now-demobilised M-19 guerrilla group took over the building and held 300 people hostage. The following military raid left 98 dead, 11 of whom were judges.

A young couple sits on a skateboard to watch the Cartagena signing ceremony live on a big screen. Since the war began in 1964, the conflict has seen many failed peace processes. While many Colombians believe too many concessions have been given to the FARC – who remain on the US international terror watch list – the accord is widely expected to be approved in Sunday’s national referendum.

A couple kiss during a speech by FARC commander Ricardo Londoño, AKA Timochenko. "Our only weapons will be our words”, the Marxist leader said in Cartagena following the signing of the deal. “In the name of the FARC I sincerely ask for forgiveness to all the victims of the conflict and for all the pain we might have caused.” If the deal is approved, the rebels will head to designated demobilisation zones to turn over their weapons to a United Nations monitoring mission.

Ramón Marín, 52, saw his family torn apart when his brother was kidnapped by the FARC in 1985. Marín’s message is one of forgiveness. “You have to release the hatred from your soul and open the door to forgiveness. That way we bring prosperity to the country."

Family members who have had loved ones disappeared by both state and guerrilla forces attend a public screening of the signing ceremony. Their sign reads, “To the disappeared: we will not forget you in peace,” Since the conflict began, at least 45,000 people have disappeared. The deal promises a bilateral search team for missing bodies.

A Yes campaigner poses in front of revellers. President Juan Manuel Santos, the face of the Yes campaign, has put his political reputation on the line ahead of Sunday’s vote. “What we signed today is a statement from the Colombian people to the world that we are tired of war, that we do not accept violence as a means to defend ideas; that we strongly and clearly saying: No more war!”

Jose Alvira Motta, 75, from the rural province of Huila, stands with a sign in support of the peace deal. Alvira served 10 years in the military and ten in the police, fighting FARC rebels and losing friends along the way. “We want to leave peace to our children and our grandchildren. Uribe and the people that follow him are filled with hatred and vengeance.”

The mood in Bogotá’s streets flickers between jubilance and sombre. US Secretary of Defense John Kerry, who was present at the ceremony in Cartagena, said “Anybody can pick up a gun, blow things up, hurt other people, but it doesn’t take you anywhere… Peace is hard work.”