The Australian doctor who brought the sexual revolution to London

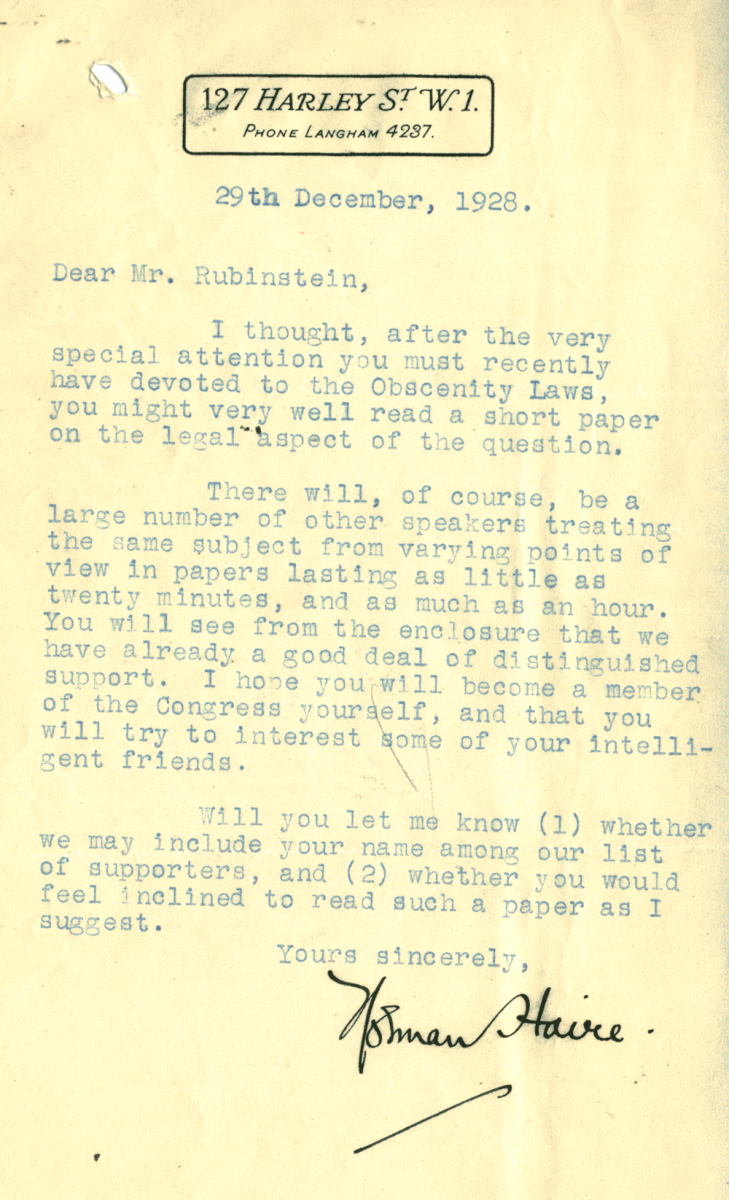

“Dear Mr Rubinstein,

I am sending you the preliminary announcement of a congress, which is to be held in London next September.

We should be very glad if you would take part in the congress, and read at one of the sessions.

Yours sincerely,

Norman Haire.”

An innocuous note, sent on 20 December 1928 from a Harley Street address to London solicitor Harold Rubinstein, giving very little clue as to the remarkable purpose. I came across this polite opening to a correspondence a few years ago, in among some other papers belonging to Rubinstein. The correspondence told the story of how Rubinstein, who had acted in the defence of Radclyffe Hall’s novel The Well of Loneliness against obscenity charges in 1928, came to be involved in one of the more peculiar moments of 20th-century progressive history.

The sender of the letter was Norman Haire, a gay, Jewish Australian sexologist, climbing the social ladder in the progressive London circles of the 1920s. He had a plan. Along with the feminist Dora Russell, wife of the philosopher Bertrand, Haire was aiming to bring the International Congress of the World League for Sexual Reform to Britain in 1929.

Norman Haire was described as a flamboyant figure and a lover of opulence

Ivan Crozier of the University of Sydney, who has written several papers on Haire and the World League for Sexual Reform, characterises Haire (born Norman Zions) as ambitious, vain and prickly. Russell described him as “a flamboyant figure, a lover of opulence”. With the hosting of the congress in London, he would take his place among the liberal elite in London. Russell, of course, was already firmly ensconced in her role as a campaigning feminist and socialist.

The World League for Sexual Reform (On A Scientific Basis) was one of those curious Fabian initiatives of the 1920s, simultaneously radical and utterly bourgeois. The listed supporters of the 1929 congress is a checklist of bien-pensant interwar literary and artistic London, from Clive Bell to HG Wells. But this was not just a Bloomsbury phenomenon.

Spanning continents, it brought together feminists, marriage reformers, birth control and abortion advocates, and gay, lesbian and even trans activists.

The leading light was Magnus Hirschfeld, a Berlin researcher who had founded the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee (Wissenschaftlich-humanitäres Komitee) in 1897, the first organisation to campaign for tolerance and rights for gay people. In 1919, Hirschfeld opened the Institut für Sexualwissenschaft in Berlin. The Institute (recently portrayed in flashback sequences in Jill Soloway’s Transparent) became a haven for Berlin’s queer community. In 1919 Hirschfeld also funded, and had a minor part in the film Anders als die Andern (Different from the Others), presented as an argument against Paragraph 175 of the German Criminal Code (“Unnatural fornication, whether between persons of the male sex or of humans with beasts, is to be punished by imprisonment; a sentence of loss of civil rights may also be passed.”)

Hirshfield's closest British equivalent was Henry Havelock Ellis. Both men had led research into what we now call transgenderism (Hirschfeld called it transvestism, Ellis went for “sexual inversion”).

In spite of the radical influence of Ellis and Hirschfeld and their explorations of sexual and gender identity, Haire, the main organiser of the conference, was keen that the congress should not focus on “abnormal” sexual behaviour.

Magnus Hirschfeld’s Berlin institute became a haven for the city’s queer community

The draft “chief planks” of the World League for Sexual Reform, most likely drawn up by Hirschfeld, included calls for “a fair judgment of those who are unsuited to marriage, above all the intermediate sexual types” and “the conception of aberrations of sexual desire not as criminal, sinful or vicious but as more or less pathological phenomenon.”

Ahead of the London congress, Haire wrote to Dora Russell that she should “draft the planks of the league’s platform in a new shape, less likely to offend the English public”. This probably explains the considerable watering down of “plank” four, the obligatory call for eugenics, which in the original had been stated as “Eugenics in the sense of Nietzsche’s words: ‘You shall not merely continue the race, but move it upwards!’”. By the time the preliminary material for the London was printed, the call had become “Race betterment by the application of the knowledge of Eugenics.”

According to Ralf Dose, co-founder of the Magnus Hirschfeld Society, it is likely that Haire intervened to edit out a reference to “tolerance for free sexual relations” for fear he might appear frivolous.

Ahead of the congress Haire asked that the League's platform be adjusted so it was less likely to offend

Haire’s personality was stamped all over the congress. Many felt that it was a stupid idea to even stage the meeting in London, which was not seen as at the centre of the debate. Some even resigned over the location. Havelock Ellis wearily wrote: “I was consulted and was against it being held. But Haire had his way. It will be, I expect, an all-Haire conference, which may be good for Haire, but not good for the cause.”

Nonetheless, Haire clearly felt the time was right for a conference on sexual matters in Britain, not least because of the controversy over The Well of Loneliness the previous year.

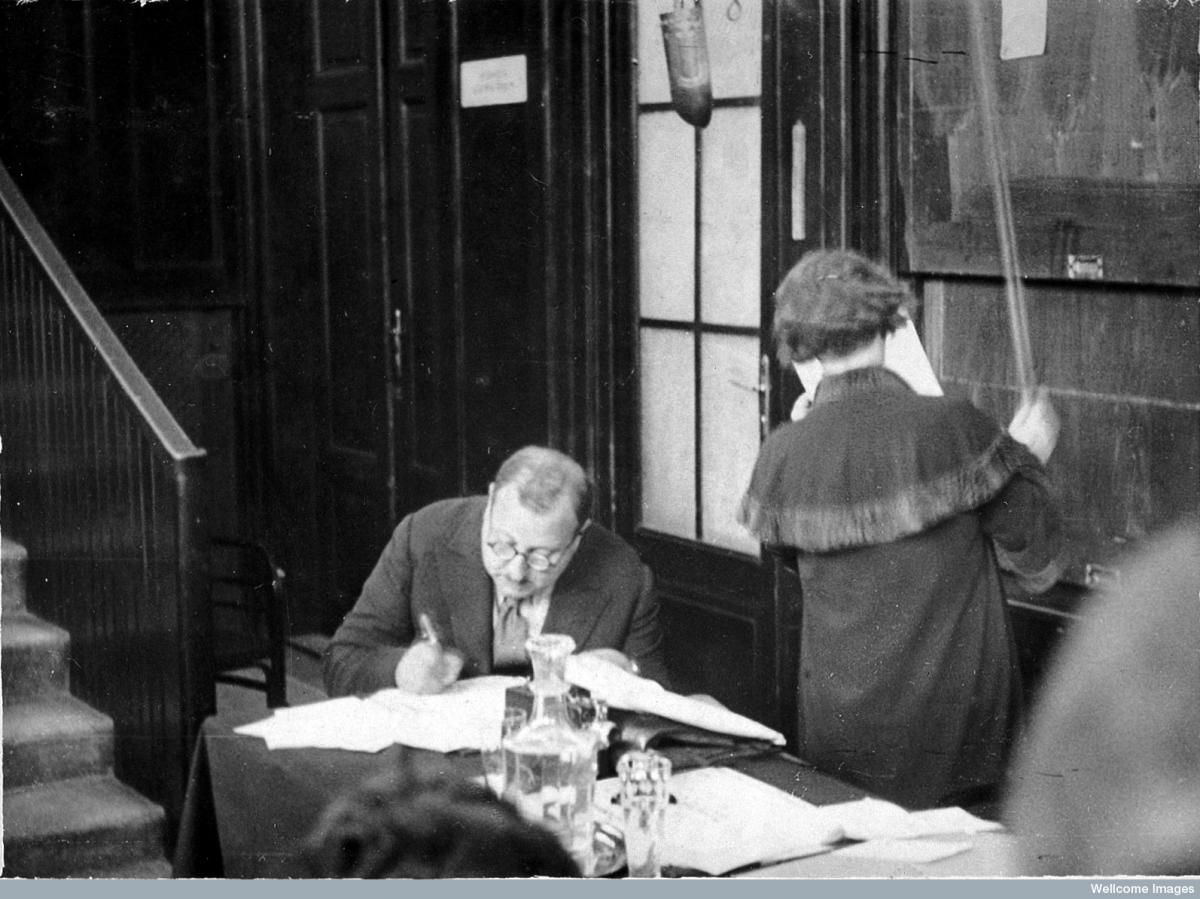

Norman Haire at the World League for Sexual Reform conference, Wellcome Library

Approaching the great and good of liberal London in the hope of securing backing for the congress, Haire wrote:

“There is so far no united body in England with an enlightened programme on sex subjects touching all sides of the question. The existence of such a group of people holding a Congress openly with foreign visitors and with the support of well-known intelligent people is calculated to have a very good effect in suggesting to the reactionaries that it would be unwise for them to suppose themselves secure from organised opposition in pursuing a policy of suppression, as in the Well of Loneliness case.”

While the likes of Ellis may have worried that there was not sufficient interest in sexual matters in London to justify hosting the World League for Sexual Reform congress, the Well of Loneliness obscenity trial had proved a rallying point for liberals. The book, concerning a lesbian love affair, was published by Jonathan Cape in a small run in 1928. Almost immediately, it found itself the subject of a campaign by the Sunday Express, which sought to have it banned.

Cape and distributor Leopold Hill were summoned to face obscenity charges, and an obscenity case opened in November 1928. Harold Rubinstein, Cape’s solicitor, sent dozens of letters appealing for expert witnesses. Norman Haire obliged, telling the court, in essence, that homosexuality was biological and that no one would become a lesbian solely because they had read The Well of Loneliness. The court disagreed, and ordered that the book be pulped and Cape and Hill pay costs. They appealed, and lost.

Shortly afterwards, Haire wrote to Rubinstein, clearly expecting a favour to be returned with a paper for the congress.

Themes included venereal disease, prostitution, birth control, sterilisation and abortion

Given this background, it is unsurprising that a large section of the programme of the congress, which went ahead at Wigmore Hall in September 1929, was given over to censorship. As well as Rubinstein’s paper, “Sex censorship and its legal aspects”, the preliminary programme also advertised GB Shaw on “Sex and censorship”, Desmond McCarthy on “The Censorship of Literature”, Ivor Montagu on “Sex censorship and the films”, Bertrand Russell on “The taboo on sex knowledge” and Laurence Housman on “Censorship of literature” (again). In fact, a whole day was given over to “Sex and censorship”.

Other days were themed around “Marriage and divorce”, “Venereal disease and prostitution”, “Birth control, sterilisation and abortion”, “Sex education” and “Modern methods of treatment of sexual disorders”. (Pleasingly, the proceedings ended with a Saturday afternoon “Motor excursion” for delegates).

In spite of the presence of early gay rights activist Hirschfeld, homosexuality was not high on the agenda, as Haire was desperate for the event to be seen as a mainstream meeting.

Magnus Hirschfeld (right), Wellcome Library

Was the London congress a success? It was, in some ways, a collision of two worlds: Haire had been keen that this be a medical conference, and that sexual issues were essentially health issues. Russell, the campaigner, saw things differently, even hoping that the congress would keep channels between Britain and the Soviet Union open at a time of increasing hostility. Haire objected, later accusing Russell of being part of a section of the WLSR that put politics above sexual reform.

But with its disparate collection of speakers and topics, and in spite of Haire’s keenness to avoid controversy, the 1929 congress can be seen as a remarkable international collaboration on issues that for their time were profoundly controversial. Reading the schedule now, the prominence given to eugenics still sends a chill. But the papers of the London congress, and the letters between Haire, Russell and Rubinstein, providing a fascinating glimpse of what exercised “progressives” in the era immediately before the rise of Nazism in Europe.

Reading the schedule now, the prominence given to eugenics still sends a chill

Did the London congress leave a lasting legacy? Ralf Dose writes that the World League for Sexual Reform's "something by everyone and for everyone" approach made successor organisations unlikely, as homosexual, feminist and birth control activists were bound to demand their own organisations for achieving their own aims. Nonetheless, he notes that many who advocated for gay rights in the 1950s and 60s has connections to the 1929 congress" "While we should not attribute to the league influence it does not deserve," writes Dose, "there is much evidence that this British branch was rooted in an intellectual milieu that was still relevant enough in 1960 to serve as an advertisement for the cause."

In the same year of 1960, Michael Rubinstein followed in his father Harold’s footsteps, acting for Penguin books in defence of Lady Chatterley's Lover. He was successful.

This article originally appeared in issue 2 of the Little Atoms magazine. To find similar articles and buy a copy, please click here.